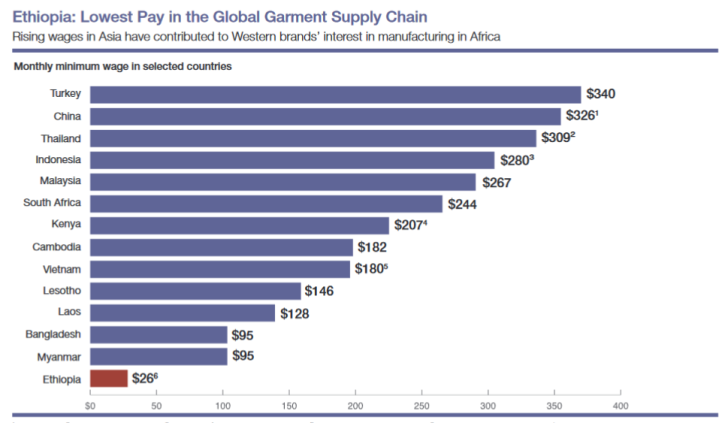

The existence of British-based sweatshops is bad enough, but the Tories, while pretending to be concerned about exploitation, are presently using our countries foreign aid budget to help establish “modern sweatshops” in distant lands. Taking sweatshop abuse to a whole other level the Tories are currently supporting the creation of mammoth garment warehouses in Ethiopia where garment workers are paid the lowest wage in the world, just $26 a month!

The Tories master plan aims to create new sweatshops in Africa which will apparently entice workers to gain a living within their own countries. As Priti Patel, the Tories development secretary put it: “If the jobs aren’t there, young Africans who are educated will want to migrate. They will want to have better prospects and futures elsewhere.” Patel made these comments while visiting Ethiopia’s flagship Hawassa Industrial Park in early 2017 — a garment complex located in a “tax-free” zone that aimed to employ 60,000 workers on two shifts. An article carried in The Times uncritically laid out the Tories plans to institutionalise modern slavery on an epic scale:

“Last year, Theresa May pledged £80 million for industrial parks in Ethiopia on the condition that a third of the workforce were refugees. The aim is to provide opportunities in the region and to stop people making the dangerous journey to Europe. Ethiopia hosts about 750,00 refugees from Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Yemen.” (“Bigger share of aid budget to be spent supporting business,” The Times, January 31, 2017)

As any sane person might have expected this brand-new state-of-the-art sweatshop did not make for a happy workforce, quite the opposite as revealed in a report published last year by the New York University’s Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. The report titled “Made in Ethiopia: Challenges in the Garment Industry’s New Frontier” noted that the site was “partly filled” employing some 25,000 mostly female workers. “PVH has created an advanced physical plant typically not found in even well-established clothing-manufacturing centers such as Vietnam and Bangladesh,” the report highlighted. Then commenting on the extremely low wages paid the authors added: “It’s common for young women to live four-to-a-room, without indoor plumbing.”

The corporations and governmental elites making immense profits from this ongoing abuse however ignore such matters of systemic abuse, and the report explains:

“For its part, PVH maintains that Hawassa ‘show[s] the world there is no conflict between companies doing well and companies doing right by the people, the community, and the environment they operate within.’ In October 2018, the U.S. Department of State gave PVH its annual corporate sustainability award, singling out Hawassa. The park will inspire ‘responsible industrialization across Ethiopia for the betterment of the entire population,’ according to the department.”

Yet the conditions are so bad that even the workers who are desperate enough to be recruited for exploitation within these new brightly lit and adequately ventilated satanic mills aren’t sticking around long. So, during the sites first year of operations “overall attrition at the park hovered around 100%, meaning that, on average, factories were replacing all of their workers every 12 months.”

On a positive front, the University report demonstrated that workers were fighting back against their exploitation; although the report’s authors assert that Ethiopia’s trade union movement “hasn’t attempted to organize employees at the industrial park.”[1] Nevertheless the workers seem fairly combative, and:

“Stability, or the lack of it, is very much on the minds of the executives overseeing Hawassa factories. Just before we arrived for a visit at Best Corporation, a majority of the India-based supplier’s 950 employees had walked out over a pay dispute. A manager was on the phone imploring a park staff member to come to the factory and talk to the remaining workers.”

Best Corporation (P) Limited (BCPL) was, it turns out, just “one of several suppliers in the park hit by strikes” on the day of the visit made by the report’s authors. In the instance of the Best dispute, workers had engaged in a wildcat strike to oppose the loss of three days’ pay from the previous week after a city-wide political shut down of the city stopped them from attending work. And their reactive self-organising paid off, as the report added: “At first, the suppliers indicated that they did not intend to pay [for the three days], but they eventually changed their minds and agreed to compensate their employees as a way of promoting labor peace.”

The aforementioned strike actions were described by the Ethiopian trade union movement in the following way:

“On 7 March, thousands of textile and garment workers went on strike at Ethiopia’s biggest industrial park, Hawassa, demanding better wages, safe working conditions and an end to sexual harassment. The workers were not represented by a trade union, because for the past two years, management at the industrial park has refused to allow unions to organize.”

The IndustriALL Global Union profile “Organizing in the garment and textile sector in Ethiopia” (May 2019) goes on to add that their local affiliate, the Industrial Federation of Textile, Leather and Garment Workers Union (IFTLGWU), “has hit a brick wall in its attempts to organize at Hawassa, despite the country’s Constitution and labour laws providing for freedom of association.”[2] Yet some such trade union reports don’t give a true reflection of limited nature of the organising efforts taking place at the factories. On this front an interesting 2019 report written by Gifawosen Markos Mitta titled “Labor rights, working conditions, and workers’ power in the emerging textile and apparel industries in Ethiopia: the case of Hawassa Industrial Park” undertakes a more critical evaluation of the union activism that is currently taking place within the oppressive HIP factories.

As part of this study, Gifawosen interviewed local workers as well as two trade unionists, one employed by IFETLGWU and the other by the Confederation of Ethiopian Trade Unions (CETU). Gifawosen corroborated the appalling working conditions previously described within the aforementioned report, with one worker arguing that “the working condition in the factory is so bad […] it seems like we (the workers) are working in Arab countries […] It is so sad that we are being enslaved in our own country”.[3] Another employee explained that “the wages are not livable […] the employers need to thank the government because they are getting our labor almost for free”.

Gifawosen however, owing to his concern with the lack of effective organizing taking place amongst the 25,000 workers at the Hawassa Industrial Park (HIP) makes the case that “the CETU and IFTGLWTU’s attempts to pressurize the government for the private sector minimum wages are nothing but bureaucratic engagements that are not supported by labor movements at the grassroot level.” When combined with the lack of knowledge and experience of organising effectively within trade unions, this has presented problems as the industrial action that does tend to take place has mostly been concerned with the “timely payment of wages” rather than dealing with strategic questions of promoting power in the workplace.[4] This leads Gifawosen to conclude:

“The assertion of the interviewed unionists regarding the mechanism they are employing to organize the workers at the shop floor level in HIP can explain this very well. Rather than making a large-scale campaign, they have been largely dependent on the good will of the employers and the state agencies in their effort to organize workers, which is literally unlikely at the moment. Whenever they have been denied, they are not able to override employers and state resistance in their effort of reaching out to the workers at the grassroots level. Thus, the unions are virtually lacking the militancy in their campaigns of organizing the workers in the industrial park.”

He adds that the lack of militancy on the part of the trade union leaderships “is, therefore, making it easy for the state and employers to neutralize the effort of the unions to organize the unorganized workforce in the industrial park.” This is a problem that faces workers across the world.

In the UK the Trade Union Congress (TUC) similarly acts to stymie militant trade union organizing. Such a passive partnership approach to trade union organising stands in stark contrast to social movement organising which has shown time and time again how “workers can militantly confront corporations and government and win.” This method of struggle is well summarised within Jane Mcalevey’s excellent book Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell): My Decade Fighting for the Labor Movement (2014). It is exactly this type of militant organising that will allow workers across the world to successfully fightback against all forms of capitalist exploitation. As Mcalevey puts it:

“Whole-worker organizing begins with the recognition that real people do not live two separate lives, one beginning when they arrive at work and punch the clock and another when they punch out at the end of their shift. The pressing concerns that bear down on them every day are not divided into two neat piles, only one of which is of concern to unions. At the end of each shift workers go home, through streets that are sometimes violent, past their kids’ crumbling schools, to their often substandard housing, where the tap water is likely unsafe.

“Whole-worker organizing seeks to engage “whole workers” in the betterment of their lives. To keep them consistently acting in their self interest, while constantly expanding their vision of who that self interest includes, from their immediate peers in their unit, to their shift, their workplace, their street, their kids’ school, their community, their water-shed, their nation and their world.

“Whole-worker organizing is always a face-to-face endeavor, with no intermediary shortcuts: no email, no social networking, no tweeting. It’s not negotiated deals between national unions and giant corporations, and it is certainly not workers waking up one day to find themselves dealt into a thing called a union that sends them glossy mailers telling them how to vote.”

NOTES

[1] After noting the lack of a presence of trade union the report adds: “In place of traditional union representation, “workers’ councils” are supposed to promote factory employees’ interests at Hawassa. But according to our inter-views, fully functional councils operate in only several of the 21 manufacturing companies. Moreover, the councils serve under the supervision of company executives and often appear to constitute the eyes and ears of management, as much as the voice of workers.”

[2] Teklu Shewarega, IFTLGWTU’s organizing and industrial relations department head said: “The recent strike is not a surprise. With no unions representing workers, low wages and bad working conditions are prevalent.

“We have tried to organize the workers for more than two years without a clear permission from the government so far. We continue our efforts and ask our international partners and the global brands and retailers sourcing from the park for support in putting pressure on the government to allow organizing.”

[3] In a footnote relating to this interview (carried out in 2018) Gifawosen explains: “5The interviewee mentioned the level of torture women are facing in Arab countries, but she indicated that it is still better to go to Arab countries than working in the factories of the HIP due to the amount of money workers are able to make there. The interviewed unionist also mentioned that most of the women are waiting for their chances to go to the Arab countries due to the alleged better income they would be able to earn.”

[4] Gifawosen writes, “these strikes often started in a certain factory and had a contagious effect on others. As the demands have usually been nothing more than a timely payment of their salaries, the strikes quickly settle whenever the management of the factories decides to pay as per the demand of the workers (I5, Personal interview 2018). This shows that strategic questions which have a substantial bearing on the interests of the workers are not being the subject of workers’ strikes in the industrial park.”